By Tiffanie Turnbull

in the Southern Highlands, New South Wales

As Australia edged into spring in 2019, former fire brigade chief Greg Mullins warned the country was disastrously primed to burn.

But his pleas fell on deaf ears, and his premonitions would come true.

Over the coming months, Mr Mullins watched on as 24 million hectares was torched – an area the size of the UK. Almost 2,500 homes burned down, and 480 people died in the flames and smoke.

Now a worrying combination of conditions has Mr Mullins sounding the alarm again.

Authorities have stressed this summer will not reach the same scale. But years of rain have caused an explosion in plant growth, which is drying out after Australia’s warmest winter on record, and an El Nino-affected summer promises more oppressively hot and dry conditions.

Just days into spring, parts of the country are experiencing catastrophic-level weather warnings.

“Bushfires will be back in the headlines,” Mr Mullins tells the BBC.

“I’m nervous.”

A firefighter’s ‘nightmare’

Out in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales (NSW), it’s not hard to see why.

Walking through the thick scrub of Nattai National Park, the occasional blackened tree trunk peeks out from behind a wall of leaves. Only by craning your neck can you see that the canopy is still threadbare. The area was incinerated four years ago.

“If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, there’s no way I would believe that had burned as hard as it did,” local firefighter Andrew Hain says.

In 2019 it resembled “the surface of the Moon with sticks coming out of it”, he adds.

“You think nothing will ever grow in there again… [but] I could now go in there 30 metres and you won’t see me any more.”

In November 2019, a lightning strike had sparked an inferno of a scale and ferocity unlike anything Mr Hain had seen in his decade in the state’s Rural Fire Service. It was relentless.

Usually, darkness brings a reprieve for exhausted firefighters – but this fire kept “burning at night like it was at midday”.

“We were working on trying to get a ring around this thing, put it in a box, but it would just keep popping out and keep going,” he tells the BBC.

By the time heavy rain extinguished it after 75 days, the Green Wattle Creek fire had burned through 278,000 hectares, killed countless animals and destroyed 37 homes. It left the communities of Balmoral, Buxton and Bargo traumatised.

Surveying the national park that borders those towns, Mr Hain points to dense undergrowth which is already turning brown, and then to the ground. It is a carpet of parched leaf litter.

“You hear that?” he says, stepping heavily. “They call that the cornflake factor, the crunch factor.”

He calls it a firefighter’s nightmare. “I look at that and I go, that is gonna burn hot, and that is gonna burn hard. If you get the right conditions, all of this will go. It could just be a lightning strike and we’re back to doing it again.”

Australia unprepared

The Black Summer, as it is known, was characterised by the unprecedented: scenes Australia had never seen before and will never forget.

Some 15,000 separate fires burned across the country, several growing so intense they generated their own weather – pyrocumulonimbus storms and fire tornadoes. One picked up a 10-tonne fire truck and inverted it, killing a volunteer firefighter inside.

Smoke clouded the sky for months, stretching as far as New Zealand and choking many Australian cities.

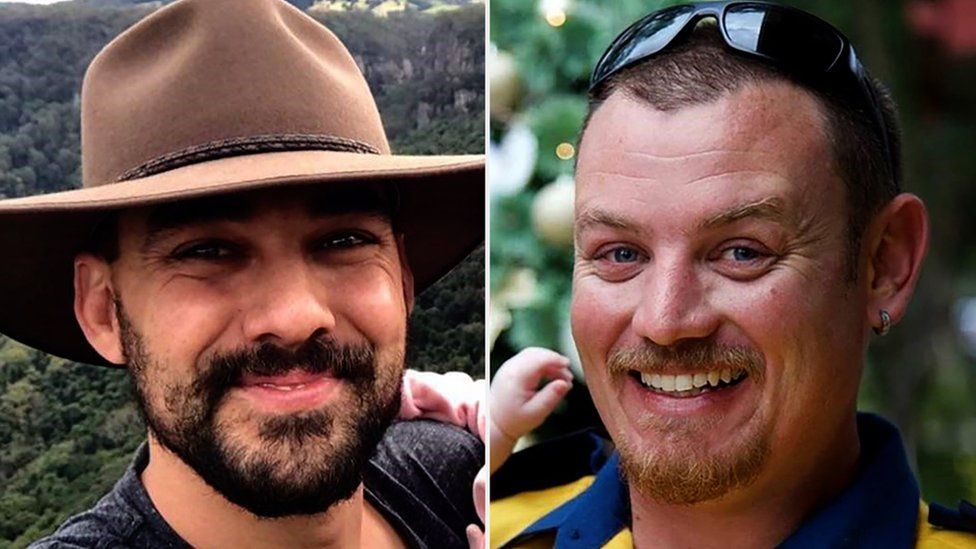

Mr Hain remembers one day in particular – when dozens of homes in his own community were destroyed and two of his peers died. Geoffrey Keaton and Andrew O’Dwyer – both young dads and volunteer firefighters – were killed when a tree fell on their fire truck.

For the first time in his career, Mr Hain grappled with the possibility of one day not returning home to his own family.

“I hadn’t considered it before,” he says.

“They got up that morning, said goodbye to their families… for what was just meant to be a shift to go and help people.”

For Mr Mullins – a veteran firefighter – the most visceral memory is driving past a traffic jam, as ten of thousands of people desperately tried to flee burning towns on the south coast of NSW.

“I just remember thinking: ‘They’re all gonna die. I’m going to come back tomorrow and there’ll be burnt-out cars everywhere full of bodies.’ I almost threw up.”

A royal commission inquiry later found a recipe of conditions had made the summer so catastrophic.

Not only did climate change exacerbate the extreme hot and dry conditions which caused the fires, it was limiting the nation’s ability to prepare for them.

Hazard reduction burns – which are controlled fires lit in cooler weather to reduce the fuel available to bushfires – have long been a key part of Australia’s arsenal. But the inquiry heard that windows of safe weather were getting narrower and narrower.

It also found Australia did not have the firefighting resources it needed – forced to rely on a largely volunteer force and overseas water-bombing aircraft to battle blazes.

Warnings to escalate

This year, Australia faces many similar circumstances.

Already, serious fires have broken out – some triggering emergency evacuations – in the Northern Territory, Queensland, NSW and Tasmania.

Although experts say this will not be another Black Summer, they have put almost the entire country on high alert.

“It doesn’t need to be a Black Summer to be dangerous. We don’t need reminders given what’s happened with the northern hemisphere fires,” said Rob Webb, head of Australia’s national council for fire and emergency services.

The general consensus is this summer will be tough, but the coming years – when the country dries out further – are the real worry.

But is Australia better prepared this time?

Both Mr Mullins and Mr Hain say governments have acted on calls to improve the equipment available to firefighters – the aerial firefighting fleet in particular.

However fuel management is another story, https://kesulitanitu.com and one increasingly out of human control. Despite the scale of Black Summer, there are still dense swathes of bushland – for example surrounding the Sydney basin – which were left largely untouched.

Elsewhere rapidly growing grass has already died and found a new life as tinder. That is the chief concern this year, experts say – the speed of grass fires can make them extremely difficult to stop.