Can a man who claimed to have seen a unicorn in the Indonesian island of Sumatra be trusted? This and other similarly valid questions have cast doubt on the truthfulness of Marco Polo since the 14th Century, when his book The Travels of Marco Polo became a bestseller and was translated into dozens of languages, hand-copied in countless manuscripts and available at any lavish court in Europe.

Polo’s tales are the first European account of the Silk Road, and they are full of wonders, spices, gold and precious stones. They also describe extravagant sexual habits as well as intriguing war strategies, making his travelogue a real pleasure to read but also partially “hard to believe”, as one particularly scrupulous amanuensis noted on the side of his copy. No need to be sceptical though. Today, 700 years after Polo’s death on 8 January 1324, we can say with a certain authority that the famed Venetian merchant, explorer, writer and self-made anthropologist indeed saw a unicorn, or at least, that he didn’t lie about it.

Venice at the time was the New York of the world

“Venice at the time was the New York of the world,” explained historian Pieralvise Zorzi, whose family traces its roots back to Polo’s time and beyond. It was an openminded and multicultural metropolis, a vibrant centre for trade between the East and the West, where the only true religion was business – and the Polo family excelled at it.

Polo’s father Niccolò and his uncle Matteo (Maffeo in Venetian) had a palace very close to Zorzi’s Grand Canal apartment, as well as offices in Constantinople that they had the acumen to close right before Greece took over the city and expelled the Venetians. The Polos sold everything just in time and went eastward looking for new markets (they would trade in silk, spices, gems and the much sought-after gland of a small animal, the musk deer, used to concoct perfumes). They came back few years later and, on their second trip to China in 1271, they took Marco, who was 17 years old at the time.

According to Polo’s text, during three years of travel along the Silk Road – from Acri (in today’s Israel) to the court of the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan in Khanbaliq (today’s Beijing) – they crossed the Middle East and good part of Central Asia. They then spent about 20 years in China, doing business and working as sort of ambassadors for the local government. They came back through Sumatra and the Andaman Islands, sailing around India before reaching Aden, Istanbul and finally Venice (see animated map below).

WATCH: The journey of Marco Polo in 60 seconds (produced and narrated by Anna Bressanin, animated by Pomona Pictures)

When they reached home, Polo was in his 40s. According to the legend, when they knocked at the door of their palazzo, the servant asked who was there, and they answered in the local dialect “i paroni” (“the owners”).

A year later, though, Polo was in jail. He had been captured by the Genovese in one of the battles between the rival maritime cities of Venice and Genoa. In prison, he had the good fortune to meet a writer and editor, Rustichello da Pisa, who saw the literary potential of Polo’s recount of a world that at the time was largely unknown to Europeans. And so, they wrote it down.

The book was a hit. The manuscript was so entertaining that it was copied multiple times and translated in various languages. Over the centuries, it became a perfect riddle for philologists, as the original version was soon lost and what was left are dozens of translations of translations, none of which are necessarily accurate.

Eugenio Burgio, who has been studying Marco Polo’s oeuvres at the Venetian University Ca’ Foscari for about as long as Polo was away from home, gave me an example of this book’s journey: a French version could be translated into a northern dialect from the region between Emilia Romagna and Veneto. This version could in turn be rearranged in Tuscan dialect. And from the Tuscan, someone translated it into Latin. How close is this Latin version to the original? It’s hard to tell, but Burgio and his team aim at publishing the first philologically complete edition of Marco Polo’s Travels later this year, in English, with the goal of offering the most plausible hypothesis and versions.

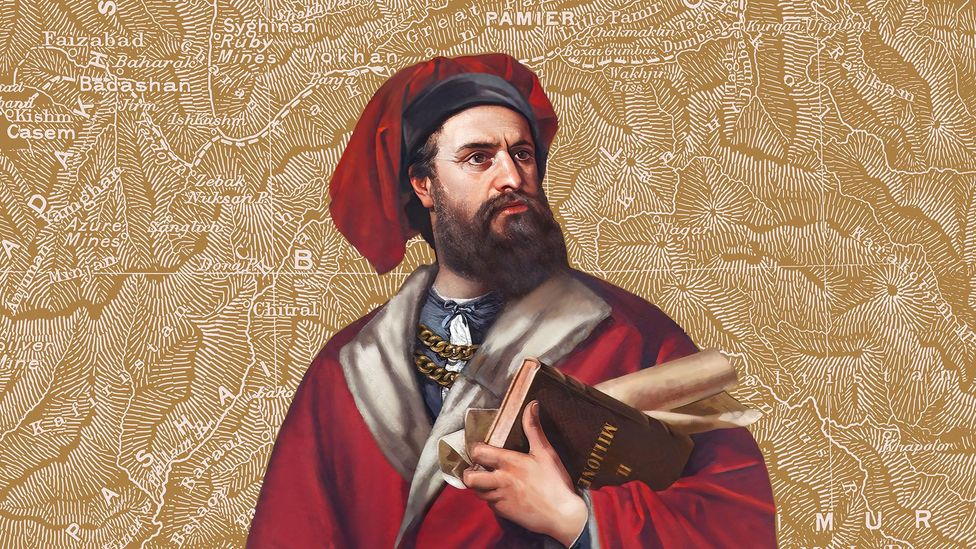

Marco Polo, the famed Venetian merchant and explorer, was perhaps the world’s first travel writer (Credit: history_docu_photo/Alamy)

“A philologist’s unconfessed dream is being a sort of Indiana Jones, unearthing treasures,” Burgio explained. And that is exactly what he and his team are doing: unearthing this literary gem written by one of the world’s first travel writers.

In the US, “Marco Polo” is a popular tag game played in swimming pools, where a blindfolded player calls out “Marco!” while trying to catch those responding with “Polo”. Curiously, the legacy of the homonymous Venetian traveller is just as elusive as the players in the game.

Not only is the original version of his book lost forever but Polo’s family palazzo was burnt in a fire in the 16th Century. When Zorzi took me on a short walk from his apartment to visit the site, we saw at least six marble plates placed on different buildings claiming to be the Polos’ house. Polo’s tombstone in the Venetian church of San Lorenzo disappeared too, and no monument in the city was ever dedicated to him.

“It’s a curse,” said professor Tiziana Plebani, who spent 10 years studying Polo and his will, written on his deathbed. And if Polo’s legacy is ethereal, the veracity of his tales has been questioned for centuries. Did he really go all the way to China, and if that’s true, how come he didn’t mention tea, or the Great Wall? He didn’t even speak Chinese, which seems unlikely for somebody who claimed to have done business in the region for quarter of a century.

Marco Polo lived in Venice’s Corte del Milion square, although his family’s palazzo was burnt in a 16th-Century fire (Credit: Robert Ray/Getty Images)

Some of these questions were raised as early as in the Middle Ages. Recently though, experts seem to agree that there are reasonable answers. For instance, Burgio is not shocked that Marco wouldn’t mention tea in his travelogue. “This thing of drinking tea is something Anglo-Saxon historians are fixated with,” said Burgio. “Why would Marco care for tea? I understand if it was wine or coffee, but tea?” Moreover, Chinese was not the language of the ruling class at the time. “And the Great Wall wasn’t finished yet,” added Zorzi.

Furthermore, proof of Polo’s travels is contained in legal papers. After the death of her husband, Polo’s daughter, Fantina, went to trial to ask for her dowry back, listing among her properties a golden passport that the Kublai Khan gave to her father. This precious tablet meant that Polo had been travelling with the blessing of the Khan. Not to mention that Polo also could describe in detail things like China’s monetary system. But while experts believe that he might have exaggerated his role of ambassador, claiming to be more important than he was, it seems that more than likely that he did make it to China.

Fantina’s story has more to reveal, though – that perhaps Polo was an early feminist. In his will, he left everything to his wife and daughters, which was unusual at the time. “It’s true that he couldn’t leave his fortune to sons nor brothers, because he didn’t have any, but he could have looked for more distant male relatives,” explained Plebani. “So, either he wasn’t in good terms with any men in his family, or he truly valued and respected his daughters and wife. It makes sense, considering that Venetian merchants would leave the city for years, and their women were trusted with everything at home.”

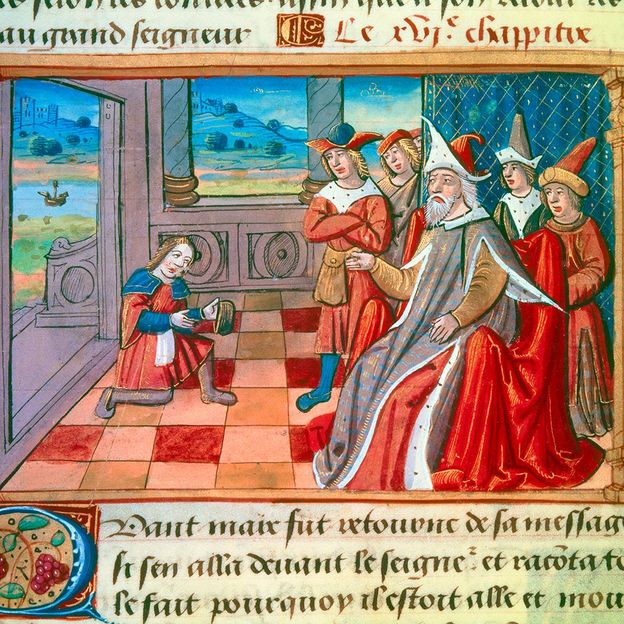

The Travels of Marco Polo detail the explorer’s visits at the court of Kublai Khan (Credit: Christophel Fine Art/Getty Images)

Although he was a medieval man, Polo describes without any judgement a region in Tebet (today’s Tibet) where no one would marry a virgin while women who had many lovers were considered the best wives, since they must have been sought after for a reason. He also marvels at a so-called Island of Women (or Female Island) in India, where men would only come to visit three months a year (March, April and May). And he would describe how Tartar women and girls in Central Asia rode horses just like men did.

Nevertheless, Polo’s interests and curiosity were eclectic, including anything “from the sexual habits of concubines to a particular kind of chicken who has fur instead of feathers”, said Burgio. He would write about the city of Sapurgan (today’s Sheberghan in Afghanistan) that had the world’s best melons that were “sweeter than honey”. He would describe the customs of the southern Indian region of Malabar, where people would wash themselves before having a meal and use only their right hand to eat. He would admire the wisdom of the Kublai Khan, who would “plant trees alongside roads”, so that travellers could easily find their way and have comfort in their shade.

Not only did he not believe that his own culture was superior to others, but he was an ardent admirer of the Mongol empire and has written about the marvels and clever aspects of each culture he experienced.

“It was the first time Polo went out of Venice,” http://nanasapel.com/ explained Zorzi. “It’s a beautiful open world seen through the eyes of an adolescent, and everything is so new, so incredibly interesting that he could record it all in his head.” Today, the world is much smaller, added Burgio, because there are almost no more unexplored corners; Polo lived in a time where there was still a lot to discover and seems to have seen humanity as a whole, noting that “people might behave differently from us, but for our same reasons”.